Harry Davis

Harry Davis was born

in Worcester in 1885. His father, Alfred, was a china figure maker who worked

for Royal Worcester and his grandfather Josiah Davis was one of the most

talented gilders ever to work at the factory. Harry started out at St Peter’s

School (where the museum is now housed) then at the age of 13, started work for

Royal Worcester. Along with all the young boys he began doing very menial tasks

and was formally apprenticed for seven years under the talented landscape

artist, Ted Salter, on 3 November 1899.

Harry started work

under the wing of his grandfather, who taught him to draw. He also learned an

enormous amount from his tutor who taught the eager young boy to paint soft

misty landscapes in the style of Corot. Harry was deeply shocked when Salter

was killed, cycling over a level crossing, on his way to work in November 1902.

Ted Salter had

reinforced Harry’s love of the countryside and of fishing. A keen fisherman,

Harry was a follower of Isaac Walton, 17th century author of the

most successful angling book of all time, ‘The Compleat Angler’. He perfected

the difficult art of painting fish with amazing accuracy, possible only to

someone with a deep understanding of fish and their behaviour. Harry was an

active member of the Royal Worcester Fishing Club and later in life painted two

wonderful trophies for the club to present to competition winners each year.

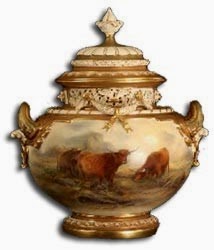

Harry quickly proved

that he had tremendous natural ability and striking individuality. He was

always versatile and painted a large range of subjects with ease. Landscapes

with sheep, cattle, pigs, fish, snow scenes, London Scenes, polar bears,

palaces and gardens, but he was never a ‘Jack of all trades’ he would accept

nothing less than perfection in everything he did.

On the 4 July

1910 Harry married ‘Cissie’ (Ethel) Powell, a dressmaker, at St Peter’s church

that stood next to the Severn Street factory. A fine watercolour of cattle

drinking from a stream, given to the couple as a wedding present by their

friend Harry Stinton, is now in the museum collection.

Throughout the First

World War there was still demand for Harrys work, but in 1916 he volunteered

and joined the wireless section of the Royal Engineers. Harry’s abilities were

quickly utilised drawing diagrams for instruction purposes, but he also enjoyed

painting postcards which he sent to his friends. On the card showing a mountain

of equipment at St.Martin’s Gate Parade Ground (just up the road from the

porcelain factory) Harry was obviously tickled by the scene before him and

commented:

Not quite clear, But very near, Next

year?

In 1919 all Royal

Worcester employees who served for their country, including Harry Davis, were

presented with an urn with their name, department and dates of service

inscribed in gold.

In 1923 Royal

Worcester received a prestigious £7,000 order from His Highness Shri

Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji, Maharaja Jam Saheb of Nawanagar. The legendary Sussex and

England cricketer owned palaces in both India and England and wanted a service

to use in India illustrating his English estate and a set to use in England

decorated with scenes of his Indian home. Harry Davis was given the challenge

and designed and painted 24 of the most wonderful scenes. He worked from

photographs, yet created views full of light and atmosphere with intricate architectural

details that were widely admired.

Harry succeeded

William Hawkins as foreman of the ‘Men Painters’ department in 1928. He was

responsible for training many young apprentices and in the early 1930s to help

with his teaching, Harry produced several sets of etchings for decorative

plates, 12 castles, 12 cottages and 12 cathedrals. The scenes were expertly

etched onto copper plates and then printed as an outline onto the china. Many

artists in the department ‘filled in’ the colours over the printed designs

adding their signature to the finished work. Sometimes Harry himself did some

of the filling in, signing himself H SIVAD, Davis backwards! Later Harry also

etched some wonderful coaching subjects and some of his favourite fish.

Joyce Holloway remembers

Harry being so patient teaching the girls to paint:

When orders were scarce during the

Depressions, and because if you were under 16 you cocouldn't claim the dole,

workers were retained and little jobs were found for them. Harry Davis gave

painting lessons to girls to fill in the time… he was very patient and he

showed me one or two little ways in drawing …and he was a very nice person [his

skills] they seemed to me incredible, they still do.

Over the years Harry

completed some very prestigious commissions for special customers. In 1928 he

collaborated with his friend Harry Stinton to complete an important order for

Mr Kellogg the American Cornflake King. Harry Stinton painted a dinner service

of 25 service plates with magical snow scenes, with rich raised gilding on a

ruby ground, and Harry Davis painted a matching dessert service of 25 smaller

plates and 25 coffee cups and saucers with delicate Corot style landscapes.

In 1937 Davis painted

some exquisite panels on the silver-gilt casket presented to Charles William

Dyson Perrins when he was given the Freedom of the City of Worcester. The

following year Harry painted a stunning vase for the Australian cricketer, Sir

Donald Bradman to commemorate his three double centuries on the New Road Ground

at Worcester and in his book ‘Farewell to Cricket’ The Don wrote

It showed the field of play, the

spectators, the lovely trees along the river bank and dominating the whole

scene the architectural masterpiece, Worcester Cathedral. This is one of my

most treasured possessions.

In 1950 Harry teamed

up with his friend Ivor Williams, the Master Gilder, to produce a jardinière to

present to Sir Winston Churchill.

Harry’s talents did

not end there. He was also responsible for the design of a number of very

successful tableware patterns. The most luxurious ‘Imperial’ with its hand

tipped raised gold, was produced for an incredible 76 years, between 1917 and

1993 in five different colours. The popular blackberry garland design,

‘Lavinia’ was made from 1940 to 1986, gold and silver ‘Chantilly’ made from

1958 and 1990 and the ‘Worcester Hop’ pattern, adapted by Harry in 1965 from a

Flight & Barr original remained in production for 20 years.

During the years of

the Second World War Harry was kept busy painting fine bone china, limited

edition models that were made mainly for the American market, to earn precious

dollars for the British economy. Harry painted many of the prototypes for

Dorothy Doughty’s series of American Bird models and Doris Lindner’s horses. He

was always a favourite of the Royal family and in 1949 he was asked to paint a

wonderful model of Princess Elizabeth on her horse, Tommy.

Princess Elizabeth

personally asked to see Harry again when she visited Royal Worcester for the

bicentenary celebrations in 1951 and in the very first honours list of the

Queens reign in 1952, he was awarded the British Empire Medal for his

contribution to British craftsmanship and design of new lines that helped the

company develop its export business.

In 1954 Ben Simmonds

took over as foreman of the Royal Worcester painting department, but Harry

continued to paint in his studio at the factory for another 15 years. In 1958,

to mark 60 years’ service for Royal Worcester, Managing Director, Joseph

Gimson, presented Harry and Ethel with a television set and much to Harry’s

amazement and embarrassment he appeared on the television himself in 1968. St John

Howell told Harry’s story on the BBC Midlands Today programme. He explained how

his first job at the factory was to wash the museum steps and he managed to tip

up the bucket and soak everything. He was very proud of the first 10 shillings

he earned, not a bit of paper, but a half gold sovereign.

What do you think I

did with it? Said Harry

Lost it through a hole in my trousers

pocket!

Over a period of four

years from 1965 to 1969, Harry took on an apprentice Rick Lewis. Harry took

Rick under his wing and shared his talents and artistic secrets in his twilight

years. Finally retiring with

failing health in 1969, aged 83 Harry Davis always stated that during his whole

time at the factory he had been extremely happy. Harry died in 1970. He was

always astonished that anyone should want to collect his work, but Harry’s

signature guaranteed the very best quality and today Harry’s name on any piece

of porcelain guarantees a high price.